Supersizing Elections

by Alex Hutchins

A political action committee (PAC) is any organization in the United States that campaigns for or against political candidates, ballot initiatives or legislation.[1] At the federal level, an organization becomes a PAC when it receives or spends more than $1,000 for the purpose of influencing a federal election, according to the Federal Election Campaign Act.[2] At the state level, an organization becomes a PAC according to the state's election laws.

In 1947, as part of the Taft-Hartley Act, the U.S. Congress prohibited labor unions or corporations from spending money to influence federal elections, and prohibited labor unions from contributing to candidate campaigns (an earlier law, the 1907 Tillman Act, had prohibited corporations from contributing to campaigns). Labor unions moved to work around these limitations by establishing political action committees, to which members could contribute.

In 1971, Congress passed the Federal Election Campaign Act (FECA). In 1974, Amendments to FECA defined how a PAC could operate and established the Federal Election Commission (FEC) to enforce the nation's campaign finance laws. The FECA and the FEC's rules provide for the following:

1. Individuals are limited to contributing $5,000 per year to Federal PACs;

2. Corporations and unions may not contribute directly to federal PACs, but can pay for the administrative costs of a PAC affiliated with the specific corporation or union;

3. Corporate-affiliated PACs may only solicit contributions from executives, shareholders, and their families;

4. Contributions from corporate or labor union treasuries are illegal, though they may sponsor a PAC and provide financial support for its administration and fundraising;

5. Union-affiliated PACs may only solicit contributions from members;

6. Independent PACs may solicit contributions from the general public and must pay their own costs from those funds.

Federal multi-candidate PACs may contribute to candidates as follows:

· $5,000 to a candidate or candidate committee for each election (primary and general elections count as separate elections);

· $15,000 to a political party per year; and

· $5,000 to another PAC per year.

· PACs may make unlimited expenditures independently of a candidate or political party

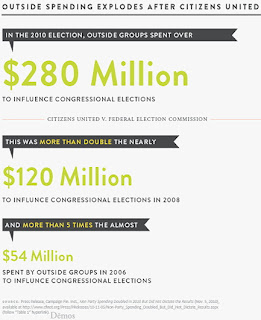

In 2010, the United States Supreme Court held in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission that laws prohibiting corporate and union political expenditures were unconstitutional. Citizens United made it legal for corporations and unions to spend from their general treasuries to finance independent expenditures, but did not alter the prohibition on direct corporate or union contributions to federal campaigns;

Most of what you hear about Citizens United v. FEC is negative. By opening the door for corporations to spend unlimited sums in elections and to allow for the creation of super PACs, the Supreme Court has made a campaign finance system that was already flooded with money much worse. But Citizens United obviously has its defenders, and they have advanced a number of arguments to try to blunt criticism of the Supreme Court’s controversial decision: The public actually learns from the flood of negative advertising coming from these super PACs; super PACS increase competition; The Supreme Court’s Citizens United decision didn’t create super PACs, so stop blaming the court for the flood of dollars and the negative campaign ads they buy. Read full article.

No comments:

Post a Comment